Concerning the new film which is due out next month, Dan Brown says in his book by the same name that the Illuminati were ‘hunted ruthlessly by the Catholic Church.’ In the film’s trailer, Tom Hanks, who plays the protagonist Robert Langdon, says ‘The Catholic Church ordered a brutal massacre to silence them forever.’ Director Ron Howard concurs: ‘The Illuminati were formed in the 1600s. They were artists and scientists like Galileo and Bernini, whose progressive ideas threatened the Vatican.’

Who were these so-called humanists, scientist, and artists? Were the Iluminati really the liberators of human reason and freedom, who pioneered against the restrictions of an oppressive Catholic regime? One of the figures of the epoch which Ron Howard's new film purports to celebrate was the quasi-scientist Giordano Bruno, who was executed under the reign of the Inquisitor St. Robert Bellarmine. As we consider roles such as Bruno's in post medieval Europe, it is important to note that the proposals of the so-called revolutionaries were not only

dogmatic in their own right and authoritarian, in the way that defies charity;

they were also profoundly anti-Christian. There is a even a striking glimpse into the whole truth of the story when we recall that, as with all of the prisoners condemned by the state to death for their crimes against the church, Cardinal Bellarmine stayed with his prisoner the night before his death, in an act of filial solidarity.

I visited the site of Giordano Bruno’s death in Campo de’Fiori in Rome as a student in college. It was a hot summer; the market booths which rim the square were steaming in the sun, offering farmer’s rustic produce on worn wooden shelves. Good Catholics were bartering their wares behind them; their saints’ medallions clanged against the iron poles of their haphazard storefronts. In the middle of the Campo, a massive bronze sculpture of Giordano Bruno stands at the site of his death, cowl down, brooding over the busy market, having been erected by the followers of Vittorio Emmanuel in a time when it was crucial to undermine Papal authority over divided Italy, whether in sculptures or in spirit. On February 17, 1600, the martyr Bruno was condemned to be burned for heresy by Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, now one of the grim models of heroic virtue who broods from a saint’s medallion, clanging against a pole in Bruno’s marketplace.

Most modern texts proclaim Bruno to be a great hero of free scientific thought who boldly confronted the Church's out-dated, anti-scientific dogma with a vision of cosmic reality, of which reluctant dogma Bellarmine was the acclaimed champion. The truth is, of course, more complex. History presents to us the stories of the judge aligned with an institution of faith, poised against the dangerous entrepreneur of science and imagination; history surprises us with their similarities. Both were dogmatic believers: while Bellarmine ascribed to the doctrine of the Christian Church, Bruno espoused a neo-Platonic synthesis of magic and the eastern theories of hermetism. The Inquisitor Robert Bellarmine may be the prototype of ecclesiastical censure of free thought in defense of dogma, but he had known his own share of censure; and we cannot help but find dogma even within the free and scientific enterprise of Bruno. Both men are now praised in their respective traditions for virtue and courage. Yet regardless of the viewer’s perspective, the historical facts are clear: there certainly is dogma on either side of the conversation. In the words of Bellarmine’s biographer Peter Godman, the roles of the (dogmatic) faithful and the (dogmatic) heretic are reversible; “on the plane of (dogmatic) ideas, the judge and the victim can be seen as doubles.”

Similarities Between the Faithful Bellarmine and the Heretic Bruno

Scholars such as Peter Godman refer to a passage in

Iordani Bruni Nolani, in which it is the heretic Bruno who assumes the role of the judge of ignorant people, a self- styled arbiter of truth and “a bearer of light to a world inhabited by the erring and the blind.” In this passage, Bruno describes himself as a presiding over a divinely ordained tribunal, which “bears an unsettling resemblance to the Holy Office served by his own judge, Robert Bellarmine.” Clearly, such a perspective is impossible to reconcile with Bruno’s perceived role as a champion of free thought; although Bellarmine and Bruno held positions which were radically irreconcilable in their respective positions as “arbiters of truth,” the inquisitor and the heretic spoke the same language. As Godman writes:

While (Bellarmine) believed that the legitimacy of his mission was sanctioned by the traditions of the church… Bruno justified his on grounds which were intellectual and individual… They both spoke a religious language, whose truth- claims were absolute and uncompromising.

The lives of the two men followed striking parallels. Both were highly educated in the classical and scholastic traditions; the same lines from Aristotle and Aquinas probably rang in their ears throughout the long course of their respective careers. Both had responded to their Christian faith with finality, both taking holy orders at a young age, both exhibiting remarkable talent in their vocations, both intimately encountering the mystery and mysticism of the Christian tradition. In their respective orders, both were known for aggressively entering the religious controversies of the day, and both were known to speak their own minds with courage and candor in matters of faith.

Godman adds that, in terms of dogma, Bellarmine and Bruno were “intellectual doubles.” Both worked within the intellectual climate of the sixteenth century, wherein prior efforts for literary elegance had given place to a desire to accumulate as much material as possible, to embrace the whole field of human knowledge, and then to incorporate it into theology. Both men sought to define coherent systems of belief in order to reform their mutual Christian faith: Bellarmine’s mission was to establish systematically and comprehensively the uniformity and unity of Catholic doctrine; Bruno’s mission was to establish the supernatural unity of the cosmos, propelled by his sense of mission as a kind of Renaissance Messiah, who would open the mind of the Church to the infinity of the universe. Both men deliberately propagated belief in their work: Bellarmine published small and accessible tracts for ready propagation of his ideas across Reformation-wracked Europe, while Bruno himself traversed Europe looking for disciples in the manner of a cult leader.

Bruno’s Dogma

The "faith" of Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) can be defined with reference to three categories: the ingenious freethinker believed in an infinite universe, an omnipresent world- soul, and the religious principles of hermetic religion.

Bruno’s metaphysical vision began with the premise of an infinite universe, in which he sought to re-unify terrestrial physics with the celestial, and to open the door to the idea of infinite human possibility. By combining religious and scientific orthodoxy with the ancient knowledge found in Platonism, oriental pantheism, and the apocryphal Hermes Trismegistus, Bruno assimilated a mystical synthesis in the form of a total cosmology. From this Gnostic cosmology Bruno derived a new concept of divinity as present in humanity and in the earth, such that humanity is caught up with God in an endless, infinite cycle of divine being and becoming, in which the matter of both the physical and the spiritual is identical, and in which physical reality is only illusion.

Bruno believed that a “continuity of influences”, the world-soul, joined the physical world, the celestial world, and the divine world in an hermetic embrace of erotic love. Rejecting the notion of ontologically separated spheres in the universe, Bruno believed that the rational human soul stood with the world-soul at the center of the hierarchy of being, to serve as a link between the corporeal world and the spiritual world, thus producing an internal and perfect unity between the cosmos and human experience.

Bruno believed that the world- soul descended from the spiritual world and gave life to the physical world, in a symbiosis through which the two worlds constantly transformed themselves into one another. From this idea of supernatural linkage, Bruno derived his infamous emphasis on magic, supernatural memory, and the role of erotic love in the perpetuation of the universe:

It seemed possible that man, endowed with a rational soul and a mediating spirit, could link himself to that privileged cosmic point on the boundary between the worlds, to grasp the archetypal forms, the generative models of every sensible reality.

Bruno also extended his concept of the universal soul to individuals, arguing that the infinite human soul originates in God and is thus immortal. Accordingly, he believed that human bodies are simply formed and re-formed again from the same matter, and that death is "nothing else than division and reunion.” Thus the human soul could return to earth in a new body after death and could even move on to inhabit an infinite number of worlds besides earth:

I have held and hold souls to be immortal...Speaking as a Catholic, [I say] they do not pass from body to body, but go to Paradise, Purgatory or Hell. But I have reasoned deeply, and, speaking as a philosopher, since the soul is not found without body and yet is not body, it may be in one body or in another, and pass from body to body.

Bruno’s new vision of the cosmos requires a change in humanity’s relationship to divinity. In the infinite universe, a relationship of reciprocal, shared necessity existed between God and man in the unity of the universe. Bruno believed that all things in the universe are connected; thus matter is itself divine, and the connection between matter and spiritual generates conceptual divinity. Furthermore, if all things between God and man might be mediated by the soul, all forms of Christology are rendered unnecessary; union with divine is possible here and now, without further mediation.

The theological conclusions of Bruno’s thought include the idea that divinity coincides with the world itself, as a divine substance which manifests itself from time to time in various modes: “If the material infinity of the corporeal were lacking, the spiritual infinity of the divine would also be absent; divinity is established as that which is all in all and in everything.”

Thus, we find Bruno acting as a sixteenth century expositor of the very old (and rather worn) heresies which Athanasius and Augustine had countered long before him. As a scientist, however, Bruno’s proposals show little promise. Biographer Dorothy Singer notes that “one wonders whether the use which Bruno made of Copernicanism might have raised in the inquisitorial mind the idea that there might be something else behind his heliocentric cosmology.” Singer goes on to state that Copernicanism was merely a symbol of Bruno’s novel religion, a means for return to the natural religion of the hermetic Egyptians within a western framework.

Professor Richard Pogge agrees that Bruno simply did not share Copernicus' scientific world view:

Much of (Bruno’s) work was theological in nature, and constituted a passionate frontal assault on the philosophical basis of the Church's spiritual teachings, especially on the nature of human salvation and on the primacy of the soul (or in modern terms, he opposed the Church's emphasis on spiritualism with an unapologetic and all-encompassing materialism). Copernicanism, where it entered at all, was supporting material, and not the central thesis. This suggests that the Church's complaint with Bruno was theological not astronomical. It was mysticism and philosophy that brought Bruno to his vision of innumerable worlds. Much of his work had little to do with astronomy. Indeed, Bruno was not an astronomer and demonstrated a very poor grasp of the subject in what he did write. What many popular accounts seem to miss is that the Church did not formally condemnation Copernicanism until well after Bruno's death. If Copernicanism were really the grounds upon which Bruno was executed as a heretic in 1600, it would have been explicitly proscribed at that time.

It thus appears that Bruno’s personal cosmology informed his espousal of Copernicus, and not the other way around. Frances Yates agrees that “Bruno’s philosophy cannot be separated from his religion;” and Singer notes that if mere belief in the movement of the earth was the point for which Bruno was condemned, his case even in this respect was in no way the same as that of Galileo, whose “views were based on genuine mathematics and mechanics” and “who lived in a different mental world from Giordano Bruno”, a world in which the scientist reached his conclusions on genuinely scientific grounds, apart from the influence of mysticism and Hermetic spirituality. Singer’s explicit conclusion is that Bruno’s philosophy cannot be separated from his religion:

It was his religion, the religion of the world, which he saw in the expanded form of the infinite universe… in innumerable worlds there lay the opportunity for an expanded gnosis, a new revelation of the divinity. Thus the legend that Bruno was prosecuted as a philosophical thinker and for his daring views on innumerable worlds and the movement of the earth can no longer stand. Completely involved as he was in his Hermetism, he could not conceive of a philosophy of nature (or number) without infusing divine meanings. He is thus really the last person in the world to take a representative of a philosophy divorced from divinity.

Bruno’s religious proposals, operating under the guise of quasi-science, were thus properly deemed to be heretical to the historical confessions of the Christian faith. In other words, Bruno presumed to advance a dogma which ran contrary to all that Christ had revealed about Himself.

Unlike Bruno, the Inquisitor Bellarmine has been called a free thinker who formed his world view around his personal faith, often at the expense of allegiance to convention. He had discovered early in his career as a theologian that veracity might be arrived at through inclusive mercy and tolerance of ideas. As a young student at Louvain, he had aggressively questioned the strict Augustinian theology concerning the total corruption of the human will and the selective mercy of God in choosing humanity by means of election. When dealing with spiritual development, he pays little attention to specifically Catholic prescriptions such as pilgrimages or indulgences; rather he urges for ascetic morality for transcendence and salvation, in this way appealing more to classical Stoic philosophy than to the particularized teachings of the Church Fathers. With some resemblance to Bruno’s belief in a “continuity of influences” which joined the physical, the celestial, and the divine in an hermetic embrace of erotic love, the sum of Bellarmine’s work has also been described as a “contemplation for obtaining Love.” Bellarmine also added an adventurous nuance to the system of divine approach in his spiritual writings, such as might have raised orthodox eyebrows, in that he promoted an image of the world shot through with God’s essence and attributes, as opposed to its merely resting under His transcendent distance:

Bellarmine’s God is not to be pictured out there without also being thought of as everywhere and especially within; he allows the reader to see that the Creator is at once infinitely above his creatures and yet utterly penetrates all the dimensions of created reality.

Even as a member of the Congregation of the Index which censured all heretical material, Bellarmine was a champion for expansive thought, requiring that exclusions of a work be decided with academic integrity; in this regard, he was frequently known to express opinions entirely independent from the more restrictive will of the Congregation. Bellarmine was a liberal scholar. One of his colleagues was known to say that he deferred to Bellarmine’s opinion because he knew everything about the heretical authors about whom he wrote daily. Bellarmine was renown for his studies in logic and philosophy, and the ability to organize his materials for effective use in the art of dispuatio.

In sum, although he was known as the “hammer of the heresies,” Bellarmine’s censorship is claimed to have been characterized by equitable restraint and humanism in an intellectual climate of denigration and savagery towards the dissidents: “implacable in exposing errors when he detected them, he was scrupulous in avoiding personal attacks on their authors.” Believing that the imposition of subjective and arbitrary opinions had led to a regress of correction, Bellarmine attempted to guide the Congregation in the direction of reason and responsibility, allowing for equivocation where shades of grey might be admitted as to a point of faith, and for the mere prescription of textual corrections where corrections were deemed necessary. Ambiguity was to be tolerated until further clarity had been decided upon through debate and consensus. Godman concludes that

"(Bellarmine’s) work is not the product of a closed mind. Doubt is admitted by Bellarmine to an extent uncommon among the Catholic controversialists of his day. Even when writing a genre little given to concession or compromise, he was capable of nuance."

Bellarmine’s concern for historical accuracy and academic integrity often led him to chastise the Congregation for the Index for its “tiresome incompetence”, as in the following words:

I detect much ineptitude in this censor. I am astonished at his acerbity in criticizing points of style which he merely dislikes. This is the way to cause irritation, not to correct error… and if (he) goes on like this, no one will dare to write anything.

On the whole, Bellarmine’s decisions as to the Index tended to be rational and often liberal, allowing for actual defense of questionable writings from time to time, as when he responded to Galileo that if science could in fact prove that the sun did not revolve around the earth, then the Church would have to willingly accept that that particular passage of the Bible should not be understood literally. According to favorable sources, what the merciful Bellarmine attempted was always censorship as rehabilitation.

Like Bruno, Bellarmine was heavily censured during his prolific career. His most famous work, The Controversies, was forbidden under penalty of death in England by the Protestant Queen Elizabeth; Bellarmine was also attacked abroad by James I for demanding a specific oath of loyalty for Catholic subjects to the crown. Bellarmine had been heavily criticized in his native Italy for undermining the authority of the Pope in temporal matters . He had personally angered several popes with his advice to promote an inclusive definition of the relationship between grace and free will, by his criticism of failures to abide by the decrees of Trent, and by his exhortation for stricter charity. Bellarmine had even been exiled from Rome for his outspoken belief. When Pope Sixtus V felt that Bellarmine’s opinions limited papal jurisdiction, Bellarmine’s work was actually included on the current Index of Forbidden Books, and only narrowly escaped permanent censure and prosecution. The Censor himself had been censured and exiled for heresy.

Bellarmine’s Faith and Bruno’s Heresy

The person and work of Bellarmine, the judge of the Inquisition, can be defined by reference to three categories: Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) was a faithful Jesuit, an ardent spokesman of the Counter Reformation, and a censor of heretical thought. In alignment with his Jesuit tradition, and the widespread motive of deepening and strengthening Catholic life and dogma throughout the world, he avoided mystical spirituality in favor of practical, common-sense moral action and catechesis. Like Augustine, he attacked magic and the Renaissance tendency towards astrologizing mysticism, and sought instead to eliminate of the veins of pagan residues and superstition within Christianity. Bruno’s theories were no exception.

As a faithful Catholic, Bellarmine defended the authority of the magisterium, the absolute precedent of ecclesiastical tradition, ecclesiastical centralization and papal primacy; scrupulous about the Summa of Aquinas and scholasticism, his mission was to establish the uniformity and unity of Catholic doctrine: “alone among his successors and peers of the (Inquisitorial) congregation, Bellarmine had developed a system.”

It is also significant to note that, contrary to his rigorous avoidance of personal experience, Bellarmine’s great mystical work, The Mind’s Ascent to God by the Ladder of Created Things, was written in 1614 as a private devotional to stimulate the reader’s imagination towards the holy.

Like Bruno, Bellarmine knew that it was possible to seek divinity in nature. Drawing from Aristotle, Aquinas, and humanist theologians, Bellarmine contemplates the marvels of the created universe in order to arouse wonder for the grand scheme of God which assists the human mind to progress up the chain of being towards contemplation and union with the One. The notion of the Ladder of Ascent echoes the ancient Judeo-Christian concept of God above and humanity below and without, requiring a “climb” upward. Bellarmine’s solution is to approach God through fifteen “steps”, beginning with contemplation of the microcosm within the human self, progressing through the basic elements, then through the heavenlies, and finally, to reach the contemplation of God Himself.

While engaging the imagination through a sensitive use of natural theology, Bellarmine maintained his strict commitment to orthodoxy by clinging to a literal interpretation of Biblical passages and, while describing the revelation of God through nature, never strayed from the implicit division between God and man; God does not so much inhere in nature (as Bruno heretically believed) as nature reflects God and provides analogies for understanding His transcendent character. By His grace through nature, God “carries man up” to Himself: “The sun gives light and heat, but God gives wisdom and charity.” Furthermore, although Bellarmine shows God dwelling in the very creature which descended from Him, the creation mainly serves to remind mankind of its own transience and insufficiency; nature is to be used to reverence and serve God, who dwells apart from it.

Bruno's Downfall

Novelty of doctrine was a significant condition of admission to Bellarmine’s censure, as was content which stood to be “plainly” condemned. Where such criteria were met, judgment was sure. Despite his reputation for equity, Bellarmine’s self-styled tombstone reads “with force I have subdued the brains of the proud.” Thus, when Bruno appeared before the Venetian Inquisition in 1592, declaring that the purely philosophical nature of his work did not implicate ecclesiastical concerns, it might have been that the Inquisitors were willing to listen to such arguments; but Bruno had come to the attention of the Roman Inquisition, which engineered his transfer to Rome for trial in 1593. There Bruno faced Cardinal Robert Bellarmine for the first time; Bellarmine brought matters to a head. He presented Bruno with a list of eight "heretical propositions" taken from his work and required him to renounce them.

The report of the eight heretical propositions has long been lost, so we do not know exactly which connections between theory and heresy were produced by Bellarmine, or on which allegations Bruno was actually convicted of his great heresy.

We do know that the “heretical” points of Bruno’s thought roughly correspond to the following assertions: that the infinity of God requires an infinite universe; that the human soul is not created ex nihilo, but is "generated" from God Himself; that the stars are divine angels; that the earth is animated by a rational over-soul; and that the universe contains numerous worlds. We also know that his promotion of magic, his identification of the Holy Spirit with the animating world-soul, and his belief that Christ was only a superior sort of magician were also significant factors in his conviction.

Furthermore, Singer adds that

"The interrogations very rarely raised philosophical or scientific points and are concerned mainly with theological queries, matters of discipline, his contacts with heretics and heretic countries; it is most certainly true that Bruno was prosecuted for matters of faith."

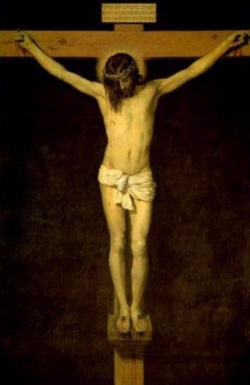

Perhaps most importantly, the theological conclusions of Bruno’s thought also extended to deny the reality of the incarnation of Christ and the real presence of the Eucharist, and ultimately negated Christianity’s declared need for a healing of the division between nature and divinity: Bruno’s cosmology even implied that Christ preached deceptively when He promised to give to humanity a transformation through which they could “become” sons of God.

Although Bruno staunchly defended his writings as purely philosophical treatments, he could not help but admit several crucial and necessary departures from Christian doctrine within those treatments, namely, concerning the separation and status of the persons of the Trinity, the transubstantiation of the Eucharist, and the incarnation of Christ. In this regard, as we can only speculate about the actual charges under which Bruno was condemned, it is helpful to describe the points at which Bruno’s theories corresponded to old and dangerous heresies which the Christian faith had been combating for generations. Bruno’s fundamental threat to doctrine, which stated that the physical reality of Christ’s incarnation was mere illusion, was not new; the issues which his theories raised were those to which the Church had responded by formulating its own statements of doctrine centuries before.

In fact, from time to time, the Catholic Church has claimed that Bruno was actually on trial for Docetism. Docetism had developed in the opinions of Cerinthus, c. 100, a Jewish Gnostic who denied the miraculous in the birth of Jesus, and proposed that the mystical Christ which “descended” on Jesus at baptism was distinct from the human Jesus Himself; Docetists were also prone to ascribe the role of a mere magician to Christ, believing that His miracles had been performed only in appearance and lacked historical reality.

The more pernicious of the accusations involved Bruno’s apparent allegiance to Arianism, which has been called the most troublesome heresy to confront the young Christian faith in its early stages of development. Prior to his fleeing his monastery and commencing his first period of wandering in 1576, Bruno was suspect for defending the fourth-century Arian heresy, a charge which was later addressed and confirmed at his trial. Arius' chief assertions centered on a Gnostic-like insistence that the Spirit who had assumed flesh in the incarnation had an entirely different nature from the divine nature of the true God, in that Jesus lacked omnipotence and eternal existence, having a lesser nature as a sort of demi- god or glorified creature.

These historical heresies would have been easily identifiable as implicit in Bruno’s doctrine of the inherence of divinity in all of nature, without the possibility of differentiation, and without the possibility of divinity or the infinite world soul inhering in only one perfect man. It seems that the scientist was flirting, not with the science of the cosmos, but with faith; he had become a heretic with a doctrine of his own.

Thus can we really look at the work of Bruno and recognize within it a neutral, purely scientific dogma which did not threaten the time-honored precepts of faith?

At this point, perhaps the Inquisition appears to be more of a legitimate contender protecting its own tradition from the “science” of Bruno, and the inimical faith which his science masked; furthermore, perhaps the Inquisition might appear almost reasonable, as an institution of learned men attempting to circumvent Bruno’s presentation of his conjecture as absolute truth. After all, Bruno was not simply asking innocuous questions; he was propagating a hodge-podge of mystical ideas, and had established himself as an arbiter of divine understanding. He was dealing in religious faith. If Pogge is correct, then “there is nothing in his writings that contributed to our knowledge of astronomy in any substantial way, indeed his astronomical writings reveal a poor grasp of the subject on several important points”. As a former member of the clergy, Bruno was certainly subject to the jurisdiction of the church regarding spiritual matters, and, as Godman writes, Bellarmine’s just efforts in Bruno’s trial were directed at identifying the core of doctrinal errors in Bruno’s writings and then explaining them to him, in order to persuade him to abjure; “in this way Bellarmine isolated Bruno’s novationism from his other and less pernicious mistakes in order to convert him.”

From the Catholic perspective, Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira writes that

Since the founding of the Church until our days, Divine Providence has always called illustrious men, who by their knowledge and sanctity have conserved and defended the truths of Catholic Faith against the attacks of heretics. St. Robert Bellarmine understood that one cannot do away with a heresy only by preaching the truth. It is also necessary to attack and smash the error. Using this method he converted heretics, bringing them back into union with the Church. When the Catholic Church canonized him, she approved this method. She said that St. Bellarmine had practiced all the virtues in a heroic degree. Since from the time of Vatican Council II, we have been taught that to attack heresy and heretics is harmful to the union of the churches. According to this conciliar mentality, every work of apostolate should praise and applaud the heretics, and never forthrightly combat their errors. The life of St. Robert Bellarmine proves precisely the opposite.

Works Cited

Iordani Bruni Nolani opera Latine conscripta, eds. F. Tocco and H. Vitelli (reprint Stuttgart, 1962)

John Patrick Donnelly, S.J., introduction, Spiritual Writings, by Robert Bellarmine (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1989)

Peter Godman, The Saint as Censor: Robert Bellarmine Between Inquisition and Index (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2000)

Alfonso, Ingegno, introduction, Cause, Principle and Unity, by Giordano Bruno (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998)

Richard W. Pogge, “The Folly of Giordano Bruno”, The SETI Online Review League (12 Oct. 1995): n. pag., online, internet, 20 Nov. 2003, available: http://www.setileague.org/editor/brunoalt.htm.

Dorothea Waley Singer, Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thoughts (New York: Greenwood Press, 1968)